Frequently Asked Questions

1. Swiss companies are innovative and successfully assert themselves against global competition. Why do we need the Pro Zukunftsfonds Schweiz foundation?

In the traditional industrial sector, jobs are being relocated to growth markets and away from Switzerland. With digitization and robotics, competition and business models will continue to change dramatically. Knowledge is Switzerland’s commodity – if it wants to keep up on the international scene in the future, it will need to rely on its innovative strength. To do this, the economic prerequisites and framework conditions can and must be improved. The foundation advocates more risk capital, optimum framework conditions for start-ups, and promoting entrepreneurship – for the benefit of future generations and their careers.

2. When it comes to research expenditure and patents per head, Switzerland is already in the lead. Why go to all this effort?

Switzerland is actually the world leader for education and research and invests more than the average in its education system and research institutes. However, the fruits of these investments, namely the patents, are only innovations if they are implemented in products and services and successfully established on the market. Innovative start-ups at the forefront of technical development currently have to go abroad in order to receive sufficient supplies and risk capital for the costly development phase.

3. What do politicians think of the Pro Zukunftsfonds Schweiz foundation’s requests?

The National Council and Council of States passed the Graber motion and the Federal Council has accepted the corresponding mandate for its implementation. The Graber motion calls for long-term assets from pension funds to be invested in promising technologies and a Swiss future fund to be created. The Derder postulate, which calls for an improvement in the framework conditions for start-ups, is also supported by the Federal Council. On October 12, 2016, federal councilors Johann Schneider-Ammann (Federal Department of Economic Affairs, Education and Research) and Alain Berset (Federal Department of Home Affairs) invited leaders from the Swiss Pension Fund Association (ASIP), the Swiss Bankers Association (SPVg), the Swiss Insurance Association (SVV), and representatives from four fund projects, including national councilor Fathi Derder as the president of the Pro Zukunftsfonds Schweiz foundation, to a round table. Together, they signed a joint declaration on promoting high-growth start-ups. The Federal Social Insurance Office (FSIO) is supporting the aims of the Graber motion with events for representatives of pension funds and fund providers.

4. Swiss start-ups get enough funding. Why do we need an additional fund?

In Switzerland, there are actually enough funds available in the start-up phase – in other words, for the initial financing of start-ups. However, there is a shortage of finance in the growth phase, where the funding requirements are much higher as ideas need to be developed into products and launched successfully on the market. So there is enough risk capital for start-ups, but not for the subsequent development phase.

5. Is there not enough risk capital already in Switzerland?

6. On an international level, Switzerland is the world champion when it comes to savings. Are the savings not invested automatically?

Switzerland saves around 30 percent of its national income. Two thirds of these savings go into collective savings pools, predominantly pension funds and life insurance policies. However, these savings do not end up in directly productive, value-creating assets. The Swiss state pension (AHV) and occupational pension (2nd pillar – pension funds) are important achievements of the welfare state; however, the roughly CHF 850 billion which are currently available in collective savings pools only end up in the job-creating cycle to a very limited extent. With just one percent of the new assets which go into the collective savings pools each year, it would be possible to close the investment gap.

7. Why does Switzerland not invest more in venture capital despite high savings?

Until the turn of the century, there were hardly any intermediaries for risk capital in Switzerland. The required savings, which are available on a long-term basis, are mainly held in collective savings pools (pension funds and life insurance policies). The majority of the approx. 2,000 pension funds in Switzerland are, however, much too small to pay the experts required for direct investments and also to invest enough to achieve appropriate risk distribution. A large fund of funds offers the necessary risk distribution and results in considerably lower costs.

8. The pension funds already invest in the economy – why should they also provide risk capital?

Swiss pension funds put their policyholders’ investments primarily into bonds (high-risk with the current interest rates), property (encouraging a dangerous price spiral), and shares of highly capitalized companies (corresponds to a change of ownership, rather than promoting innovation). Swiss pension funds currently only invest 0.02 percent of their resources in venture capital. In the USA, pension funds invest up to 5 percent of their assets in venture capital funds – they do this with a long-term outlook and above-average returns.

9. Are risk capital investments not too risky for pension funds?

An individual investment in a start-up is actually associated with a high risk of loss. In general, only 5 out of every 100 companies enjoy great success; however, these compensate for the failure of the others. If you distribute the funds across 100 professionally selected investments, the profit/loss ratio is normalized. Insurance companies are an example of this successful risk distribution. The individual risk is cushioned by the critical mass of a large number of policies. The envisaged fund of funds can be compared to reinsurance, which is no longer affected by individual risk. A small pension fund must therefore not invest in individual venture capital products or even individual start-ups; instead, it must do this through a fund of funds which invests in professionally managed venture funds in promising sectors.

10. Pension fund assets are subject to government regulation. Are the allowed to invest in venture capital? What effects do initial losses have on the coverage ratio?

Pension funds are currently able to place up to 5 percent of their assets in what are referred to as “alternative assets”. This group of assets also includes venture capital investments. Pension funds have a performance mandate with quarterly reporting. Assuming a risk capital commitment of less than a percent of the total assets, the impact of a lack of return in the first 10 years is minimal for the individual fund. However, it has been suggested to the legislator that the accounting loss should be neutralized and the investments in venture capital should be stated at cost value for the first 10 years.

11. Do governmental obstacles prevent investments in start-ups?

Yes, particularly taxes like stamp duty, wealth tax, loss carry-forward periods, and progressions, but also accounting valuation rules. As a result, concrete (in buildings) can be capitalized, for example, but intellectual property cannot. Pension fund managers must therefore manage their venture capital investment as a loss for 10 years, which is why they are shying away from the economically attractive form of investment. Paradoxically, our tax system prefers debts to capital.

12. Are there enough eligible start-ups and projects in Switzerland? Is it not risky, just investing in Swiss start-ups?

There are enough ideas and patents but too few elaborate projects as there are too few venture capital companies which define and structure the projects and therefore shape ideas into feasible, promising projects. This needs a great deal of expertise and work, as well as skills other than those possessed by the researchers and inventors. Making “project ideas” into good projects requires highly qualified, experienced experts. As in Silicon Valley, the capital from the Swiss future fund will also attract foreign start-ups, particularly from countries in continental Europe which are wary of risk capital. The same applies to venture capital companies. This pull means that it is possible for the Swiss future fund to place at least 50 percent of the assets in start-up companies in start-ups in Switzerland. For risk distribution and networking reasons, the remaining 49 percent can be invested abroad, primarily in Europe.

13. Which start-ups should be funded?

The Swiss future fund is not a general finance mechanism for start-ups. That’s what banks are for. It provides advice, support, and finance for innovative start-ups at the forefront of technical progress – those which have 10 to 12 years of uncertainty and can generally not record any profits in this period. There are two large collective savings pools which can provide this sort of long-term capital which is vital to the future: life insurance policies and pension funds, both of which have long-term savings (up to 40 years) at their disposal.

14. Does Switzerland have enough demand for a CHF 500 million fund?

In 2016, VC projects amounting to more than CHF 907 million were financed. The biotech sector alone took more than CHF 300 million and demand has increased sharply in recent years. As soon as word gets out that there is venture capital in Switzerland, many venture capital companies will flock to Switzerland, just like they currently do to Silicon Valley.

15. Are venture capital investments attractive?

Over 60 percent of all venture capital investments in Switzerland were financed by foreign venture capital; Switzerland is clearly fertile ground for promising technologies. A large proportion of Swiss start-ups emigrate so that they can be financed abroad, mostly in the USA. Switzerland produces lots of attractive start-ups.

The annual average return on American venture capital investments has amounted to 17 percent (index) in the last 30 years. Professionally managed venture capital companies have existed in Switzerland since the turn of century. As the investments from the first 10 years are registered as losses, the average return from the first 16 years is still temporarily lower than in the USA.

16. Why do venture capital investments result in high costs (TER)?

While buying shares on the stock market only incurs a low brokerage fee, direct investments in the real value-creating, employment generating economy are very costly. A venture capital company analyzes, for example, 100 projects in the pre-selection phase. After selecting 10 of these, it then choses the best project and finances and supports this. However, it’s the return which is key, not the TER.

17. Will a fund of funds not increase the costs unnecessarily?

Thanks to its size and the broad distribution, the fund of funds works like an insurance policy and the commission like an insurance premium.

18. Why do we need venture capitalists as risk capital intermediaries?

The venture capital system, which is around 50 years old, have proven itself in free-market economies, predominantly in English-speaking countries, as the ideal instrument for promising direct investments in the real economy.

19. Why should the Swiss future fund only invest in start-ups at the forefront of technical progress?

Swiss prosperity is largely based on the export of high-quality and unique products in sectors in which the Swiss economy has invested billions in research and development over a period of decades and Switzerland is at the forefront of technical progress on an international level.

Over the last two decades, the capable Asian competition has caught up considerably through copying and it is conceivable that they will be able to make modern-day Swiss products at a lower cost in 10 to 20 years. To maintain prosperity, Switzerland must intensify its investment in promising, value-creating products, systems, and services.

50 years ago, 90 percent of our modern-day products did not exist and at the time, no one would have believed the extent to which they would change the world (the cell phone, for example). At our world-class technical universities, ideas are born everyday. Thanks to start-ups and venture capital, these will create jobs for the next generation.

20. Why does Israel invest around USD 4.5 billion per year in risk capital whereas wealthy Switzerland only invests USD 700 million?

Innovation competition has, indeed, intensified on a global scale. According to ETH President Professor Patrick Aebischer, politicians are unwilling to actually implement declarations of intent in Switzerland. The Graber motion (suggestion of a Swiss future fund) was passed unanimously by parliament back in 2014. Not a lot has happened since then; the wheels of bureaucracy turn slowly – hopefully not too slowly.

21. How long will the dry spell be until the investments in venture capital come to fruition or start generating returns?

In the first 10–12 years, investments in promising innovations at the forefront of technical progress must be posted as losses in Switzerland. Swiss pension funds have a very short-term investment horizon, unlike American, Canadian, and Swedish pension schemes, which have a much longer-term investment outlook. For pension funds which invest the capital of a policyholder over 40 years, the 10–12 years of “losses” are sustainable. In the subsequent 28 years, they achieve an attractive average return, even taking the initial years of loss into account.

22. In which sectors on industries should investments be made?

In areas where Switzerland is already well-positioned due to existing industrial activities and also in areas where there are opportunities for the future thanks to the promising output of its research institutes. Start-ups in the energy and green technology, new materials, nanotechnology, IT and robotics, biotechnology and life science, and medical technology sectors are at the forefront. The Board of Directors of the fund of funds can change this selection from time to time.

23. Who decides on the sectors in which investments should be made?

The Board of Directors of the Swiss future fund limited partnership for collective investments. This determines the strategy and is made up of members who are involved with the development of innovative technologies, visionaries who are anticipating technologies which do not even exist yet, companies, and representatives of the investors and the legal and financial sector. They define the investment policies. The management company appointed by the fund of funds decides on how the resources are allocated to the VC companies.

24. A fund of funds is expensive. What will the Swiss future fund cost?

The costs of the fund of funds stem from the professional risk distribution. This also applies to insurance companies, for example, which receive a premium for the service. Risk distribution protects against damages and means the institutional investors can invest in the future. The fund of funds including the management company, which allocates the resources to the various venture capital companies, should cost barely 0.5 percent on average for the first 10 years. The management of the venture capital companies should cost approximately 1.5 percent, the same as equity funds from banks. The reason for the relatively low cost is the critical mass or fund size.

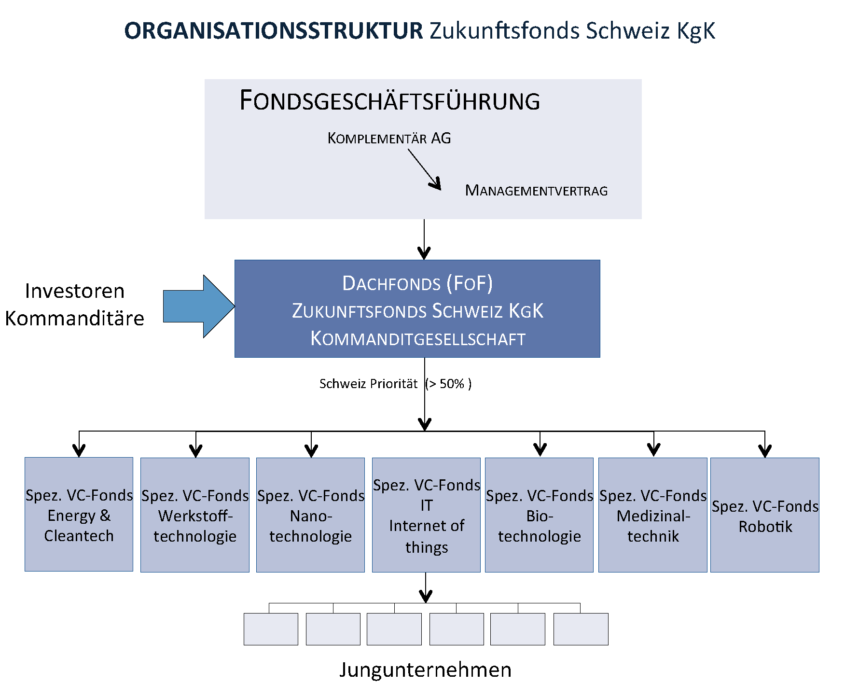

25. How is the Swiss future fund organized?

The fund of funds invests in specialized venture capital companies in the individual sectors through the management company. The VC companies in turn invest in the subsequent development phase of promising start-ups. It is a limited partnership. The Board of Directors of the fund of funds, which defines the strategy, is made up of representatives of the investors and also experts who are at the forefront of technical development. The management is delegated to a professional management company by means of a management contract. The graphic below shows the organizational structure.